Walking home from work I am struck by the silence. Two white wardrobe doors sit horizontally against a low wall, their doors frosted glass or plastic. The front garden with the tall hedges on three sides sends out its watery sounds; there is a hidden fountain inside and miniature raised beds holding secret vegetables or perhaps new flowers. It is always colourful in there because passersby can’t see it.

Ahead there is an ambulance with its left-hand side fully open, a side door wound up and lights shining out into the late afternoon, somehow alive in a way I’ve only seen in films. Two police cars flank it, both empty with their lights turned off. One is pulled in towards the pavement at a sharp angle as if it stopped in a hurry but now all its urgency has gone. Three police officers loiter on the pavement. Their voices murmur like the water of the fountain a few doors down. I cross to the other side of the road, walking past a man waiting by the parked cars. As I pass him he starts to follow, a few steps behind me.

Foxes, he says.

I don’t say anything.

There was a fox just up there, eyeing me.

I look at him as if to ask if he was scared, and he says, I wasn’t scared, but have you seen that video? Of a man getting chased by a fox? Nasty.

I tell him I’ve not seen it. Something in his voice is warm. He’s in a light puffer jacket and black jeans, headphones on.

It was watching me, see?

We look around as if we might find it. My road is coming up.

They always congregate here, I say, and it’s true, though you don’t normally see them until later.

We part at the corner and he says goodbye as I say good luck, and then he says good luck too. At home all the lights are off; I’m the first one back. I unpeel myself from my clothes, step into the shower, feel the air warm up. I dress and make tea and sit at the kitchen window.

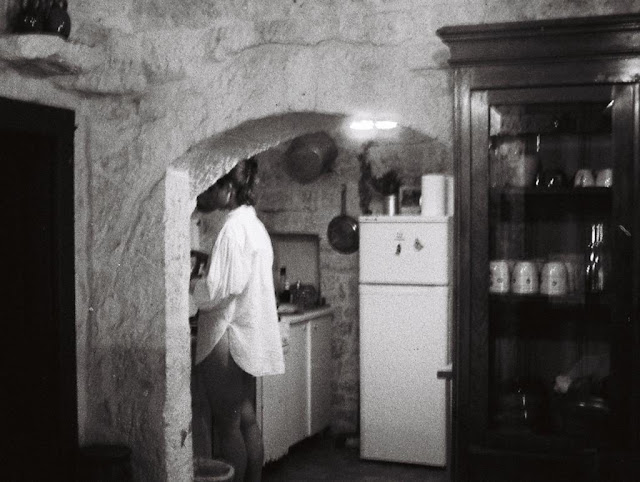

In my peripheral vision, there are handprints on the walls. Bodies from warzones fertilise the soil; their skin feeds the vegetables. I cook spinach and sweet potatoes and black beans and not one of these things grew locally. I wonder when local became both insult and aspiration, as I look more intently at the marks on the wall – no, they are footprints. Sole prints from attempted inversions, toe marks trailing down the paint. I still can’t do handstands without the solid support of a bare wall, but I’m trying. The flat downstairs opens and closes its front door with an anonymous, high-pitched thanks bye, meaning the Australian woman whose name I can’t remember must be in after all, though I believed myself alone in this building, walking up and down singing loudly, always reinventing songs from a past life. I wonder what she’s received and think of all the letters I used to send out into the world, all the notes and torn-out scraps, all the ink on paper, all the hands my words have passed through. His scarred fingers.

I walk through late sunlight, past a house plant whose leaves sound papery as we move against each other. I think of him elsewhere in the city, moving through the same light. I dreamt about him last night; he’d grown larger and my mum was there. She told me she regretted all the things she’d never said to him and went up dream stairs to find him, to tell him that no, she was angry actually, so angry the anger might never stop, but in the dream I told her it didn’t matter. Over messages she often tells me how sorry she is – I should have warned you off; I should have told you to leave, to get out of there – but it wasn’t her fault. Whenever I have these dreams I think about relaying them, but one of my colleagues at work whose older years and panoply of stories are eternally appealing told me that dreams aren’t for analysing, but for the processing of the soul. I wash my hands and light a candle. Train sounds mix with late builders packing up across the road.

The dream residues are less enduring now. I dream that I have a complicated but not bad-natured conversations with people from the past. When I tell new friends about the life we used to live, they look confused. They’re not what I was expecting, my housemate tells me. She studies their faces on her phone screen, having searched for them on Instagram, pinching the pictures to make them bigger. They all look very… normal. I tell her I can’t imagine a life where I didn’t know what it felt like to go down to the living room every day and find them sitting there in musty dressing gowns with greasy hair and plates of scraps on the arms of the sofa.

The front door opens and closes again and my housemates filter in. I hear them chattering, hear music filling the kitchen, hear my voice being shouted up the stairs, and: still ready for nine?! We’re going out.

Everyone told me it would take a year and a half, maybe two, to be over it. I realise, now, that this sense of moving on is more like moving away, as I struggle to remember the contours of the kitchen sink or the hob at which we cooked. I cannot conjure up his laugh, no matter how hard I try. I struggle to remember him as anything other than a collection of words and walks and body parts which only exist in the memories of the ways they touched me. Perhaps this is normal, or perhaps it isn’t.

Tonight, we’re going out to dance in a gallery that stays open late into the night, and when that closes we’ll walk along the river to a smaller venue where the rooms are warren-like and the music changes with the lights. We’ll wear matching suits without meaning to. We’ll know all the words.

Sometimes I wonder if my brain is still in the throes of breaking down, working through the slow violence of his aftermath. I Google it, of course, and learn about the causes of unexplained tinnitus. I learn that I might experience overeating, undereating, anxiety, slowness of breath, quickness of breath, insomnia, lethargy, hopelessness, and depression in the wake of it all. At least he left his mark, perhaps he’ll muse, as he completes his order on Deliveroo or sits on his swivel chair, laptop screen dimming, late light glazing the lower ground floor window. His room will smell of salt, or maybe the women he sleeps with will give him generically wood-scented candles for his birthday.

When everything closes, I’ll suggest that we stay up. We’ll stumble to the nearest station and catch the earliest train to Brighton. The sky will be getting lighter but we’ll race down to the seafront anyway and catch the last of the pink dawn reflected in the sea. The pebbles will be damp through our clothes and we’ll plunge our hands into the water to test the temperature. It will bite. As the promenade fills up with people on their morning runs we’ll go in search of coffee and breakfast.

I’m ready before the others so I make drinks for us all and watch the sun going down. My candle has a few minutes left to burn. I watch them both until the light disappears.